True to his religious convictions, Simon Bizimana, a farmer from Gisoro hill, Twinkwavu zone in Cendajuru commune (Cankuzo), refused to register for the vote on the referendum in May. He was arrested, then died on March 18, 2018, in the provincial hospital as a result of “acts of torture”, according to human rights activists. From malaria, the authorities retort. Two Iwacu reporters conducted a field investigation.

By Fabrice Manirakiza and Rénovat Ndabashinze

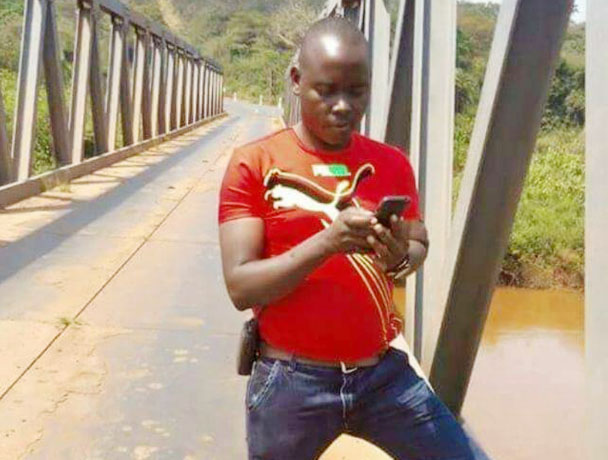

Simon Bizimana

At six o’clock in the morning, we set off from Bujumbura. We’re heading in the direction of Cendajuru, Simon Bizimana’s commune of origin. We have no address, no contact with the family.

From the start, we felt that the case was very sensitive and people were reluctant to talk, let alone be seen with journalists. Several people we tried to contact from Bujumbura told us: “It could cause problems for us.”

But after pleading repeatedly, we managed, with difficulty, to establish a few contacts.

Investigating a high profile case is not easy. As we leave Bujumbura, news of the Simon Bizimana case is spreading on social networks, which have jumped on the story. It is “buzzing”, as they say.

We are aware that we are entering dangerous ground. None of the three of us – the driver and the two of us – is reassured. We listen to gospel music in the car, to try to relax a bit. The road from Bujumbura to Cankuzo is long. We don’t talk much in the car.

Finally, we arrive in Cankuzo. The road is stony. There are steep bends and hills. You have to drive slowly. We stop somewhere. We don’t know exactly where the family lives. We have to make a few phone calls.

Our contacts are reluctant to meet us. They ask to meet us at about 15 kilometers from the capital of the commune. We don’t have any choice, we have to make do. We know we can’t rush them. If our sources get scared and turn off their phones, we will return to Bujumbura empty-handed.

Our sources are suspicious. They lead us from one place to another. We know they can see us and are watching us. We don’t know them. They probably want to make sure that we really are journalists.

At one point, our contact tells us to stop and to wait somewhere. After a few minutes, a man shows up and asks us: “Which media do you work for?” We had already given our identities. We give them again. The man is thinking. The suspense is terrible. Everything is playing out in that moment. “How do I know you’re not going to denounce us later?”

In our investigations, we never pay for information. We have to be able to create trust, to convince people. We understood that if the man “vanished”, our investigation in Cendajuru was over, before we’d even started. So we deliver the most summary and most convincing “précis of the ethics of journalism”.

In Cankuzo, people are afraid. Too many “important” local figures have been named in this case. The case is sensitive.

In Cankuzo, people are afraid. Too many “important” local figures have been named in this case. The case is sensitive.

After thinking for a few more moments, our source is finally convinced. He gives us a few tips to move around “as incognito as possible”.

From then on, everything goes well. Despite the fear, people are reassured and collaborate fully. Even better, they are admiring, touched, and tell us how much “they like and respect true journalists who leave Bujumbura to find out who killed a simple ‘munyagihugu’ (peasant)”.

In fact, we realised that at first, they didn’t believe in us; they suspected they were being tricked… The investigation can now begin.

In search of Simon Bizimana’s family

We head in the direction of Gisoro hill. You have to go through the capital of the commune. At about 5 km, we’re blocked. It’s a Saturday. Young people are doing community work. Most of them are wearing CNDD-FDD party T-shirts. Impossible to go forward or turn back. We have to wait. An hour later, we can move on.

But in the depths of this Burundian countryside, news travels quickly. The arrival of “strangers”, — and, what’s more, “journalists” – does not go unnoticed. We are spotted. Our contact person is worried. We are afraid he may give up.

We tell him that to avoid causing problems for the family of the deceased, we will meet them elsewhere, not at their home. Somewhere on a different hill. In the house of a family acquaintance. Our contact is reassured. We can breathe. It was a lucky escape.

Judith Nibigira: “I want to be told the truth about my husband’s death.”

Finally, she arrives. Judith Nibigira, the young widow, is 29 years old. She is barefoot, wearing a worn but clean wrapper. Simon Bizimana’s wife first wipes a few drops of sweat from her forehead before greeting us. She had to travel a few kilometers to find us at this improvised meeting place.

She is carrying her youngest child, four months old, in her arms. The child is crying. He has difficulty breathing. He seems to be sick and feverish. “He’s been like this for a week. A neighbour gave me a few pills, but his condition is not improving.”

The young woman cannot afford medical treatment for him. “I relied on my husband for everything. My children are going to die”. And she starts crying in front of us.

Before we can ask a single question, she starts telling us about her woes, about her house that is on the verge of crumbling down. “Simon was planning to restore it this summer. It’s going to fall down on top of us.”

We look at each other. We hesitate to question her. Her brother-in-law, Théodore Nduwimana, looks at her, hides his eyes with his hands and discreetly lets a small tear fall. We’re paralysed by so much pain and misery. We’re stuck, we can’t question her.

Ten minutes go by. Total silence. Finally, it is Judith who encourages us to speak. “I want to be told the truth about my husband’s death.”

Our journalistic reflexes return. We start questioning her, and she is willing to speak.

Who is Simon Bizimana?

Simon Bizimana is the son of Pie Kinyakura and Mélanie Minani. He was 35 years old and the father of five children. The oldest is ten years old. Simon was a farmer and apolitical. He made a living doing odd jobs like ploughing neighbours’ fields.

According to his wife, he was a staunch Christian; he belonged to a kind of “prayer brotherhood”. Neighbours said this very peaceful brotherhood was made up of three people. “They organised prayers at the house of one of the members on a rotating basis.” A man with no history, he was not known to have any conflicts in the neighbourhood.

A look back at Simon Bizimana’s death

The testimonies of his wife, of his brother-in-law, of the neighbours, and information we cross-checked in Gisoro, Cendajuru and Cankuzo enable us to reconstruct the tragic death of the farmer Simon Bizimana.

On February 14, 2018, a video spreads on social media. It shows a man kneeling, a Bible in his hand, responding to questioning by a person whose face can’t be seen.

“I said that under no circumstances should a man of God participate in elections. Jesus said: happy are those who are persecuted for righteousness, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. Rejoice, for your reward will be great in heaven.” It was Simon Bizimana, trying to explain himself on the day of his arrest.

Contrary to what the police claimed in a tweet on March 19, 2018: “He was arrested by @BurundiPolice for obstructing the electoral process on 14/2/2018”.

Simon Bizimana de @CankuzoProvince est mort de la malaria. Il était en liberté provisoire chez lui depuis près d’une semaine. Il avait été arrêté par @BurundiPolice pour entrave au processus électoral le 14/2/2018. Il n’a jamais été torturé et était sorti de prison en bonne santé pic.twitter.com/HdIEUxjNWb

— Burundi Police (@BurundiPolice) 19 mars 2018

Arrested for “obstructing the electoral process”? False

The deceased did nothing of the sort, according to different testimonies gathered in Gisoro. “He wasn’t even interested in politics. He never did what he was accused of”, says his wife.

The residents of the hill confirm this. They describe a peaceful man who always walked around with his Bible. “We never heard him talk about politics.”

So what happened? On February 14, one morning, while the family is still sleeping, they are woken up at six o’clock by two local administrative officials: Isaac Nkurikiye and Marc Nimpa.

Nimpa is the chief of Gisoro hill. They ask Simon Bizimana: “Did you register for the referendum vote?” The farmer politely replies that he cannot, that his religious beliefs forbid him from voting.

The hill chief calls the administrator of Cendajuru commune, Ms Béatrice Nibaruta. “I’ve been ordered to take Simon Bizimana to the capital of the commune.”

So Marc Nimpa, the hill chief, hands over the farmer to the head of the police post in Cendajuru commune, Donatien Rirabakina, and the commune administrator.

Simon Bizimana’s ordeal is about to begin. The farmer will not return to Gisoro alive.

Beatings

The police post in Cendajuru commune, Donatien Rirabakina

According to our investigations, Simon Bizimana arrives at the capital of the commune on February 14, in the multipurpose room of the commune where the video was filmed.

According to our sources, the voice questioning him in this video that hit the headlines is that of the head of the police post in Cendajuru commune, Donatien Rirabakina.

Simon Bizimana is on his knees, humiliated, but still refuses to register for the vote and clings onto his Bible.

After this public humiliation, which was described and confirmed by several eyewitnesses, he is led into the woods behind this multipurpose room. There, he is “seriously beaten”, said several sources.

The population points to the head of the police post in Cendajuru commune and the commune administrator, Béatrice Nibaruta.

When we question him, Donatien Rirabakina refuses to speak, “referring us to the police spokesperson” before hanging up on us.

The commune administrator is more talkative. She insists that Simon Bizimana was not beaten: “No one touched him, neither during his arrest nor during his transfer to Cankuzo. Everything was done peacefully and without any brutality.”

Yet several eyewitnesses say the opposite. “She used an iron bar and the Bible of the deceased” to hit him. Simon Bizimana was bleeding from his nose when he was taken to Cankuzo.

Transfer from Cendajuru to Cankuzo

Simon Bizimana spends the night of February 14 in the cells of Cendajuru commune. According to several sources, the next day, he is beaten again by the head of the police post along with Ms. Nibaruta. He was still bleeding from his nose and ears.

Witnesses describe a poignant scene just before he was taken away in the car of the chief of the National Intelligence Service (SNR) post in Cankuzo, Bonaventure Niyonkuru. With blood flowing from his nostrils, Simon Bizimana called out at his wife: “Yudita (Judith), ask for forgiveness for me so they can release me!” But Judith couldn’t do anything.

Simon Bizimana’s pleas do not move those who arrested him. He is taken away with two other people accused of obstructing “the electoral process”, including Melchior Ngwirahara. Simon Bizimana is taken to the capital of Cankuzo province.

But he is already in bad shape. “In the car, he told me he wasn’t feeling well. When I looked at his ears, there was blood,” says Melchior Ngwirahara.

When they arrive in the city centre, they are questioned by the local SNR chief. Simon Bizimana is questioned last. In the evening, they are taken to the cells of the provincial police station.

Different sources all confirmed that he was never detained in an individual cell. His wife confirms this. “When I went to see him, he was held with other prisoners in a room. We spoke through a wire fence. He wasn’t allowed to go outside, and I don’t know if he ever received the meal I brought for him.” Simon Bizimana would spend 28 days in the detention centre of the provincial police station in Cankuzo.

He told his wife he was not doing well. “I could see it too. He didn’t look well,” says Judith Nibigira. He wasn’t eating much. He also had trouble sleeping.

“One day, he told me he was having difficulty chewing. Eating caused him pain in his jaws,” said a former cellmate, who has since been released.

His companions in misery in the cell in Cankuzo detention centre say they twice warned the police to take him to hospital, but each time, the police turned a deaf ear.

His cellmates state that he was not tortured at the Cankuzo police station. However, they said he was never brought before a judicial police officer (OPJ) throughout the entire period of his detention. Simon Bizimana’s condition would get worse and worse.

Hospitalization

Since Monday, March 12, 2018, Simon Bizimana was on the list of detainees who were supposed to receive medical treatment, but this was never done, even as his condition worsened.

At around 8 a.m., on Wednesday, March 14, 2018, Simon Bizimana loses consciousness. He collapses onto the floor like “a sack of sweet potatoes”, say his cellmates. They start screaming and calling for help.

The police don’t seem to be in any great hurry. “They came to pick him up at 11 am,” said sources at Cankuzo police station.

Death

Simon Bizimana arrives at the emergency department at Cankuzo Hospital at 2:45 p.m. “He was brought in by two policemen. He couldn’t even walk,” said nurses at the hospital.

He was quickly hospitalized in the general department “because the nurses saw that he was in terrible shape.” Simon Bizimana arrived in a critical condition, unconscious, according to the nurses who received him. Some suspect internal bleeding as a result of the blows he received. “When I went to see him, I saw that it was already over,” says Judith Nibigira, his wife.

We were able to interview a few patients who saw him. They confirm that when he arrived, “he was unable to speak, let alone eat.”

Simon Bizimana died on Sunday, March 18, 2018, at 1 a.m.

Justifications

Simon Bizimana’s death is causing a stir on the web. Human rights activists don’t hold back. Questions fly in all directions. Grey areas are also noted. The police is accused of “murdering Simon Bizimana after a month of torture and ill-treatment.”

Backed into a corner, the police explain on Twitter: “Simon Bizimana from @CankuzoProvince died of malaria. He was never tortured and was released from prison in good health.”

Simon Bizimana de @CankuzoProvince est mort de la malaria. Il était en liberté provisoire chez lui depuis près d’une semaine. Il avait été arrêté par @BurundiPolice pour entrave au processus électoral le 14/2/2018. Il n’a jamais été torturé et était sorti de prison en bonne santé pic.twitter.com/HdIEUxjNWb

— Burundi Police (@BurundiPolice) 19 mars 2018

Donatien Barandereka, the provincial police commissioner in Cankuzo, even offers additional information. “I am not a doctor to determine diseases.”

According to him, Simon Bizimana was arrested in Cendajuru. He was accused of inciting the population not to register for the referendum and the 2020 elections. Then, he was handed over to the prosecutor’s office, which carried out its own investigations.

These investigations did not produce substantial evidence implicating him in the subversion of the population. “He was then cleared, and returned home to his family.”

Mr. Barandereka says there is a release document, without specifying the date of Simon Bizimana’s release. He says that it was after this that he fell ill and was hospitalized in Cankuzo Hospital. “His death certificate says he died of malaria.”

As for Léonard Sindayigaya, the prosecutor in Cankuzo, he simply refers us to the spokesperson of the Prosecutor General’s office.

When we contact her, Agnès Bangiricenge states that the file has been closed. “He was granted provisional release.”

This story of “provisional release” leaves his family and the residents of Gisoro speechless. No one ever saw Simon Bizimana alive again, except his wife, at the detention centre in Cankuzo. “The day before his death, his wife came to see him at the detention centre. We told her he was in hospital,” say his co-detainees.

Béatrice Nibaruta

Of all the explanations for the death of Simon Bizimana, the commune administrator’s is unique. We have the sound recording; some would find it hard to believe that these words were actually spoken: “I think he was haunted by demons. Because maybe he broke satanic law by saying he didn’t believe in elections. He was a victim of that,” the commune administrator told us, in all seriousness.

> Listen to the administrator answering questions from the Iwacu reporters

[wonderplugin_audio id = ”374 ″]

We were bewildered. Before our eyes, she tried to correct herself: “He may have starved to death as a result of the detention conditions that he wasn’t used to. Because of his beliefs, he said he couldn’t eat tubers, for example.”

The family declined to comment on the administrator’s remarks.

The funeral

On Sunday morning, March 18, a member of Simon Bizimana’s family receives a message from the hill chief. Simon Bizimana is dead. The impoverished family does not know which way to turn. They can’t afford the funeral. “As he died in the hands of the state, we thought that the commune would take care of the burial,” say the farmer’s relatives. So the family appeals to the commune administrator. Béatrice Nibaruta rebuffs them sharply. The Twinkwavu zone chief also raises the question of bringing the body back to Cendajuru. It’s no use. On Monday, March 19, 2018, the residents of Gisoro organize themselves. “We were able to collect 135,000 Burundian francs to rent a car and buy a coffin,” says Simon’s brother. Simon Bizimana’s remains return to Gisoro, covered only with a cloth his wife had left him the day before. “It was a nurse who returned the body to us. They didn’t asked us for anything else. We put the body in the car and drove off. ” Helped only by the driver of the rented vehicle, his brother was able to bring the body back to Gisoro. The burial took place the same day at 4:30 pm. Neither the hill chief, nor the zone chief, nor the commune administrator, no one was present. Simon Bizimana, 35 years old, father of five, a farmer by trade, rests in the small cemetery on Gatare hill.

IWACU Open Data

IWACU Open Data