Investigative reporters from authoritarian regimes across the world who attended the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Gothenburg, Sweden this year say they face threats. They call for global collaboration and solidarity.

The 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference officially kicked off this Wednesday September 20 with a keynote address by Ron Deibert, founder and director of the Citizen Lab cyber security research unit at the University of Toronto. He enumerated several surveillance threats- driven by a new commercial espionage industry–faced by investigative journalists all over the world.

According to him, the smartphones journalists have come to depend upon “have also become your greatest source of insecurity, thanks to the mercenary spyware industry.”

For him, privately-developed and government-deployed hacking and geolocation tools are now so powerful. Hence, there a little people can do to prevent their phones from being secretly hacked.

He recommended that investigative journalists with iPhones immediately enable Apple’s new “Lockdown Mode” which helps protect devices against sophisticated cyber-attacks.

Deibert said democracy is in retreat in different countries, and the rule of law is under threat, as despotism and impunity keep spreading.

“We need to remind ourselves that investigative reporting, responsible disclosures, and other work that we all do together can have a huge impact. Our collaborations are something to celebrate,” he said.

As for David Kaplan, outgoing executive director of Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN), press freedom is under threat in most countries in the world.

According to him, GIJC is an opportunity for investigative journalists to know that they have a global support.

“In whichever country you work, know that you’re not alone. Investigative journalism is more needed than ever before. Together, we will advance it.”

Independent journalism remains a dangerous profession in Burundi

Investigating and exposing sensitive topics like human rights violations, corruption, (in)security related issues, etc. in Burundi is dangerous, as this may infuriate the power. Hence, many media give in to self-censorship, while others choose to do entertainment.

The 2015 political crisis has had a negative impact on the media landscape in Burundi. There was a harsh repression against media outlets which were suspected to collaborate with the opposition. Many were destroyed, others set ablaze on May 14th, 2015, a day after the failed coup. A hundred of journalists were forced into exile.

Many journalists who stayed in the country gave in to fear of repression. Some left journalism for NGOs or other businesses.

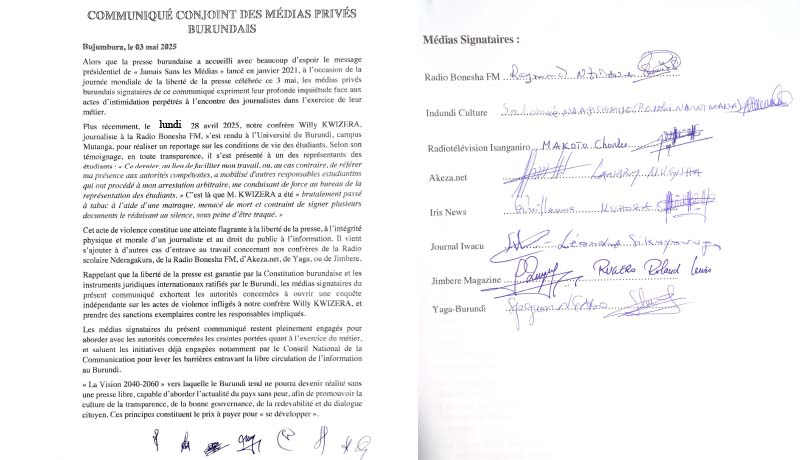

For a few media and journalists who kept working independently, they have sometimes faced several threats. Iwacu, one of the rare independent newspapers operating in Burundi, has always been in the crosshairs of the Burundi media regulatory.

On September 20, the Burundi media regulatory (CNC) accused Iwacu newspaper among other media like RFI, of committing professional mistakes without informing the media of the so committed faults. However, several media, whose professionalism is not their first quality, nonetheless escape the vigilance of the CNC.

Besides, Iwacu journalists are oftentimes subject to intimidation, arrests, imprisonment and even kidnapping.

In November 2015, the Attorney General announced that Iwacu press group director, Antoine Kaburahe, was « involved in the May 2015 coup attempt” and issued an arrest warrant against him. The founder of Iwacu managed to leave the country in extremis.

Jean Bigirimana, an Iwacu reporter, has gone missing since July 22, 2016. Until this time, no clue about him. Later in October 2019, four Iwacu journalists were arrested as we investigated the aftermath of a rebel incursion in the northwestern province of Burundi. We had to arbitrary serve one year and two months of prison.

Almost two years after our liberation, Floriane Irangabiye, another Burundian journalist working for a radio station in the neighboring Rwanda was arrested on August 30, 2022 by the National Intelligence Service’s agents.

After a few days in the intelligence services’ dungeons, she was taken to Mpimba central prison in Bujumbura before being transferred, on October 3, 2022, to Muyinga prison in northeast Burundi where she is still jailed to date.

Same sad reality elsewhere

In Benin, Burkina Faso and Suriname, investigative journalists are still threatened through arrests, imprisonment and physical attacks. News outlets are shut without having committed any professional mistake. The situation is the same in countries/states ruled by authoritarian regimes and oligarchies.

Jason Pinas, a Suriname’s investigative journalist, says he was beaten by bodyguards of the vice president, Ronnie Brunswijk in December 2021.

“I took a picture of him giving money to one of his followers and he didn’t like that. He got very angry and started buzzing me out. All of a sudden, his bodyguards attacked me and physically abused me.”

Two weeks after, he adds, some people dropped hand grenades outside his home. “Since then, I’m being very careful about what I report on politics,” says the GIJC23 fellow.

In Benin, press freedom regresses. On August 31, police officers in Benin’s northwestern Pendjari national park arrested and detained Damilola Ayeni, a Nigerian editor at Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), as he was taking pictures at the park for his reporting on environmental conservation.

The officers accused him of involvement with a jihadist terror movement and held him at the police station in the northern city of Parakou, until September 5, when they moved the journalist to Cotonou, Benin’s largest city. He was released later on September 8.

According to Ignace Sossou, a Benin investigative journalist working at CENOZO (a west-African investigative journalism network based in Burkina Faso), the imprisonment of Ayeni was unfounded and unfortunate.

This GIJC23 participant also deplores that the government of Burkina Faso (resulting from a coup d’état) recently suspended the broadcasting of Radio Oméga, one of the most listened to in the country, after the broadcast, on August 10, of an interview that, according to the government, “contained insulting remarks against the new Nigerien authorities.”

Ignace Sossou also says that investigative journalism in Benin is so perilous and fragile.

“Access to sources of information, especially official ones, is now a big challenge. This makes investigative journalism hard in this country.”

He calls on investigative journalism to stay the course, despite all challenges they may face throughout their work.

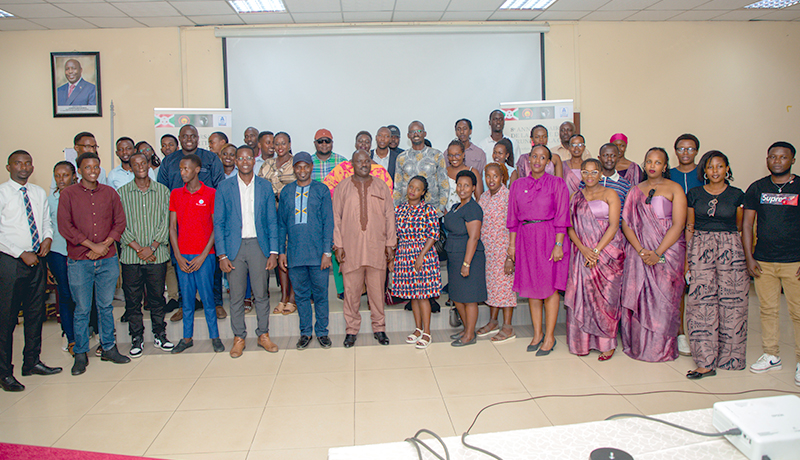

The 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference gathered, from September 19-22, 2,138 investigative reporters and editors from 132 countries, making it the largest gathering of watchdog journalists on record. It featured over 200 expert panels, workshops and networking sessions.

This conference also marked the occasion for David Kaplan to pass the baton to the GIJN’s new executive director, Emilia Diaz Struck.

Also, stories on illegal mining in Venezuela, systemic banditry in northwestern Nigeria, police brutality in South Africa, and COVID-19 profiteering in North Macedonia won Global Shining Light Awards (GSLA). The prize honors watchdog journalism in developing or transitioning countries, carried out under threat or in perilous conditions.

The Global Conference is held every two years. Since the first gathering in Copenhagen in 2001, the GIJC has brought together more than 10,000 journalists from 140 countries.